COVID-19 End of August Update: Testing

Sep 2, 2020

As we enter the Fall season with the end of Summer and school starting, we send our sincere greetings and good wishes to all of you. A lot of us have had to make more complex decisions about issues that are usually thought-free. Do I send my child to school? Can I see my grandchildren? We appreciate that the extra effort on these decisions often sacrifices brain power on other matters, such as your personal health and well-being. We’re here to support you! Please reach out and ask any questions you have. We’re always happy to talk, whether in person or on the phone or on video chat.

Before we get into the COVID update, I want to talk about flu shots. We always recommend flu shots. Every year. The only reason NOT to get a flu vaccine is if you have an allergy to one. This year is no different. One primary reason is to decrease the number of influenza-like illnesses that could be confused with COVID. The fewer times any of us are worried about illness/testing/quarantine/risk, the better.

We recommend you get the flu shot at the end of September/early October.

We want the shot to last until the end of the flu season in March, and if you get it too soon there’s a chance it could wear out before then. We will send out an announcement when it’s time to get it, AND where. We will have it in our offices.

So, what about COVID testing? There have been some very public changes to the CDC’s recommendations on testing and some new versions of tests that are hitting the market. Ten-dollar self-administered kits, the UofI saliva test, and more. We will say this: The Harper Health team does NOT ascribe to the new CDC guidelines on limiting the testing of asymptomatic people.

It might be good to start with a story of a patient who called me recently. The patient lives with his now-21 year old son. His son went out to the bars last Saturday for his 21st birthday. The son was a bit worried about exposure so he got tested the following Wednesday and tested positive. So, my patient needs to quarantine for 14 days, yes, and his son needs to isolate for at least 10 days. Should my patient be tested? According to the new recommendations from the CDC, the answer would be no because he has no symptoms. We think that’s wrong.

Who should get tested?

Symptomatic individuals: People who have symptoms that are consistent with COVID-19 should be tested. The symptom list hasn’t changed much in the past month. The main symptoms are still fever, cough, shortness of breath, with other symptoms that have been added over time. If you lose taste or smell, that’s a fairly specific sign that you have the illness.

Contacts: This is where the controversy comes in. We believe that if you have had close contact with someone who has subsequently tested positive for COVID-19 you should be tested. What is close contact? It is a "close contact" if you have been within six feet of someone with COVID-19 for over 15 minutes. This contact must have happened within 48 hours of the individual developing symptoms or testing positive for COVID.

Surveillance: This is what’s being done in colleges and some lower schools. You test people who have no symptoms and no known contacts. In this situation you’re trying to find ill people without symptoms who could unknowingly spread it to others.

When should someone be tested?

Symptomatic: If you’re symptomatic, you should test right away. Don’t wait. In fact, if you do wait, the chances of finding virus go down.

Contacts: This is an important issue and has come up a lot with our patients. I mentioned this in a blog post a time back. If you get the test too soon, you may get a false negative result. The situation is common: You were with a friend at lunch, they call you two days later to say they tested positive. You call and say, “I want to be tested today.” The chances are that the test on that day will be negative because the virus hasn’t had enough time to replicate in your system and be picked up with our tests. The recommendation is to wait somewhere between 5 and 8 days before you test. In the past I recommended day 5 and 10, but given the turnaround time on the test, it seems almost best to get tested on day 7 or 8, just one time. If you’re negative (depending on the test chosen), you’re likely to be good

Surveillance: There is no timetable on this. Typically people go by the protocol defined by their team/institution. Here at Harper Health we test every two weeks. (All good!)

How should they be tested?

This is the important question and worth spending some time discussing. No test is perfect. The idea of “accuracy” requires a little understanding of statistics, and I apologize in advance. In the best case, you want a test to pick up every person who has the disease (sensitivity), but avoid mistakenly testing positive those who don’t have it (specificity). Different tests have different levels of sensitivity and specificity depending on how the test is performed and what you’re testing for.

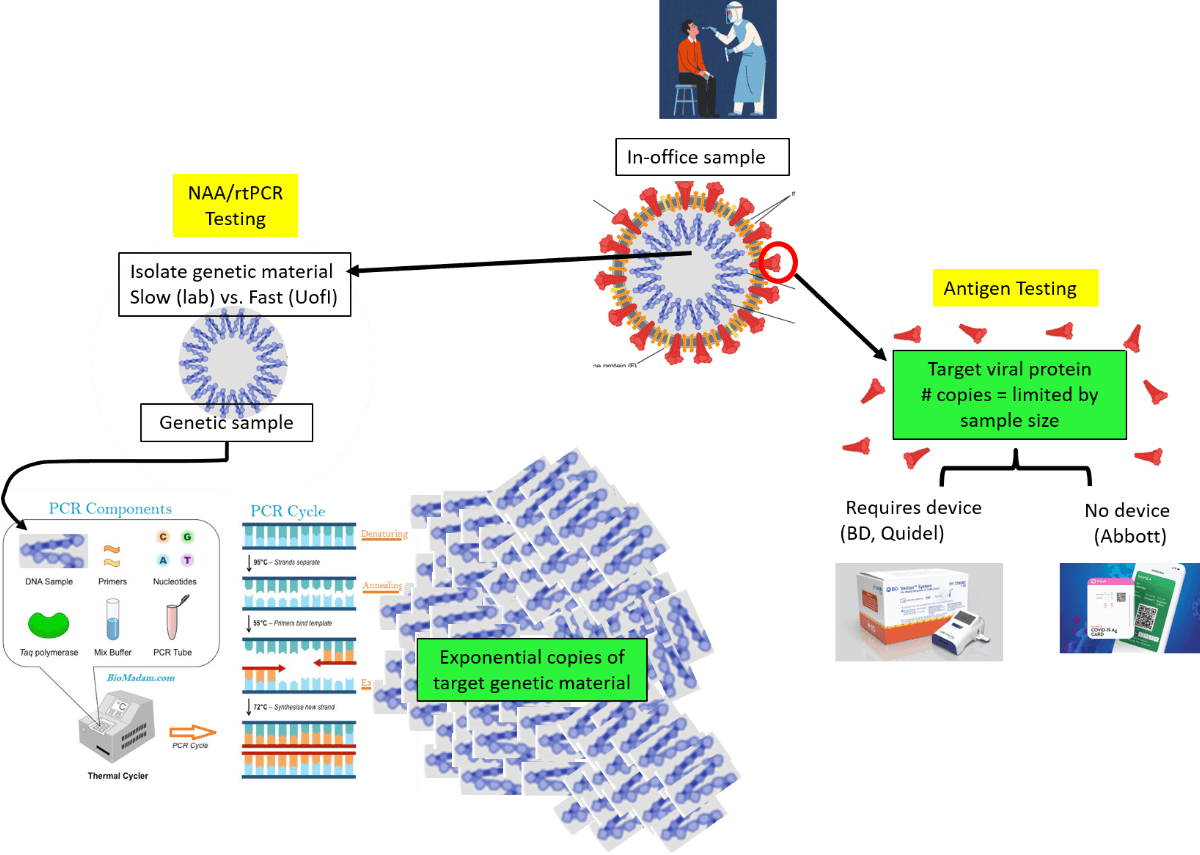

The following photo shows the two different diagnostic approaches to COVID-19: NAA/rtPCR/molecular testing and antigen testing. Apologies for how small this appears on mobile devices.

Antigen testing. With antigen testing, the test looks for a very specific protein in the material tested. An analogy to antigen testing is a pregnancy test. When a woman becomes pregnant the body starts producing a protein called human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG). Home pregnancy tests take advantage of the fact that the protein is not in the urine of non-pregnant women. The test has detectors for the presence of the protein, and if it’s noticed it will turn the test positive. For the new COVID antigen test, the we will take a sample from the nose (not the urine) and the test will look for the presence of a SARS-CoV-2-specific protein. The test can quickly be done at the point of care. We are working on acquiring antigen tests for the office.

The limitation of antigen testing is the presence of enough antigen to turn the test positive. If a woman does a pregnancy test too early, the test may be negative. The same goes for COVID. The antigen test will give you a false negative if you don’t get a sample from a location in the nose with enough virus, or the illness isn’t far enough along where there’s enough virus on the swab, or the opposite: the illness has progressed too long and there's less virus in the nose. Also, an antigen test is designed to be specific to a particular protein associated with the virus. A protein similar to the SARS-CoV-2 protein could create a positive result in the setting of no disease.

Nucleic Acid Amplification testing (NAA)/molecular testing. With NAA, the test isolates and amplifies the genetic code of the virus and then applies a tag for a SARS-CoV-2-specific segment of this code (rtPCR). With NAA, fewer copies of the virus need to be present for the test to be positive. Therefore, the sensitivity for NAA is higher (fewer false negatives). Plus, since the test looks for a virus-specific segment of genetic code, fewer false positives are also detected (higher specificity). This test is the GOLD STANDARD for testing for COVID.

There are a few limitations of the NAA. First, there are the same limitations of sampling. If you don’t get a good sample, you won’t detect the virus. In addition, this process is usually two steps: isolating the genetic material and then amplifying and tagging it. The first step requires a biohazard-safe lab, trained lab technicians and reagents that are in limited supply. The second step requires an expensive machine. The new “rapid saliva” test that has been used at the University of Illinois is an NAA test, but it’s fast because there’s a novel technique to bypass the biohazard-safe lab/time/labor/reagent-intensive genetic code isolation step. Here at Harper Health we have purchased a machine that is safely able to do both steps in one – we should have the device by this upcoming flu season and will give results in 35 minutes. So, depending on the type of device and the setting of the test, the result for NAA could come slow or fast.

So, what test should you choose?

Symptomatic: The NAA is the gold standard, so if possible, this test should be done. However, you want the patient to know they have COVID so they can identify their contacts. Waiting several days for the NAA to be performed at an outside lab is not ideal, so an antigen test would be good in this situation. Since the individual is sick, there’s a good likelihood that there is a lot of virus around, so the chance of a false negative is lower. If the test is positive, then it’s very likely the patient has disease. If it’s negative, typically the provider will send a second sample for NAA.

Contacts: For contacts who have no symptoms you want a test that has high sensitivity, given the amount of virus present may be low. So, again, the NAA test is best. The patient will be in quarantine already, so a test with a quick turnaround time is preferable but not absolutely necessary. You do want a reasonable turnaround time, though, so the individual can tell their contacts to quarantine.

Surveillance: If you can get same-day NAA, this test would be best for surveillance. Why? First, it’s got the highest sensitivity and specificity. Second, there’s extreme value in same-day results. Think of a college campus: if it takes a couple of days to get a test back, by the time it does the student may have already exposed quite a few people. So, a test that gets results faster is key: The device we'll have in the office will be good for surveillance. The UofI saliva protocol is also a good one, as the sample can get into the rtPCR machine without need for a biohazard-safe lab, with less processing time and with reduced labor. While the antigen test would seem to be inadequate for this purpose, it can be a good strategy if it’s employed frequently in the screened population. If a person doesn’t have enough virus to test positive, they probably don’t have enough to infect people. So, if you’re using an antigen test frequently, say twice a week, you can capture folks with the quick antigen test right at the time they could infect people.

So, what about my patient? The CDC’s new recommendations suggest he should not be tested because he is not symptomatic. Yet what if my patient, himself, has asymptomatic infection now and doesn’t know it? If he does, this means people he was with up to 48 hours prior to when he started quarantine have been exposed. If he’s positive and doesn’t test, they don’t know that they were exposed and can perpetuate the infection cycle. My patient could just tell everyone that he MAY be positive, and they should quarantine. But if they’re in quarantine should they tell THEIR contacts to quarantine? How far back do you go? So, the test is critical. If my patient tests positive, he can properly tell people he has tested positive for COVID-19 so they can quarantine and get tested themselves. In the assessment of most public health officials, frequent testing, contact tracing and isolation is how we end this.

Please continue to be safe. In the past two days we've had two COVID-19 cases in the Harper Health community. Please wash your hands. Please wear a mask when you'll be in close contact with people. Please keep a social distance. You can't tell by looking at someone whether they'll have the fever of COVID-19 in 48 hours. If they end up having COVID-19 and you haven't kept your distance, you've been exposed.

We've had one death from COVID-19 in the practice. We want to keep that number right where it is.

More updates to come,

Dr. Will

Sign up below to join our newsletter